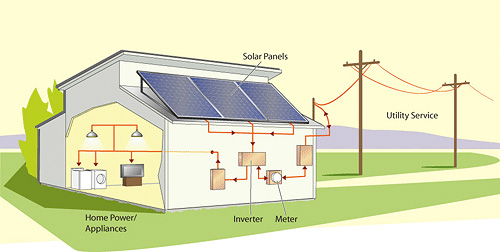

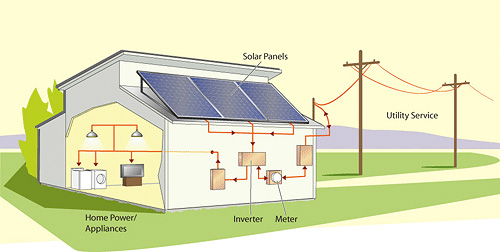

A photovoltaic system, also PV system or solar power system, is an electric power system designed to supply usable solar power by means of photovoltaics. It consists of an arrangement of several components, including solar panels to absorb and convert sunlight into electricity, a solar inverter to convert the output from direct to alternating current, as well as mounting, cabling, and other electrical accessories to set up a working system. It may also use a solar tracking system to improve the system's overall performance and include an integrated battery.

PV systems convert light directly into electricity, they are not to be confused with other solar technologies, such as concentrated solar power or solar thermal, used for heating and cooling. A solar array only encompasses the ensemble of solar panels, the visible part of the PV system, and does not include all the other hardware, often summarized as balance of system (BOS).

PV systems range from small, rooftop-mounted or building-integrated systems with capacities from a few to several tens of kilowatts, to large utility-scale power stations of hundreds of megawatts. Nowadays, most PV systems are grid-connected, while off-grid or stand-alone systems account for a small portion of the market.

Operating silently and without any moving parts or environmental emissions, PV systems have developed from being niche market applications into a mature technology used for mainstream electricity generation. A rooftop system recoups the invested energy for its manufacturing and installation within 0.7 to 2 years and produces about 95% of net clean renewable energy over a 30-year service lifetime.

Due to the growth of photovoltaics, prices for PV systems have rapidly declined since their introduction. However, they vary by market and the size of the system. Nowadays, solar PV modules account for less than half of the system's overall cost, leaving the rest to the remaining BOS-components and to soft costs, which include customer acquisition, permitting, inspection and interconnection, installation labor and financing costs.

Components of Photovoltaic System

- Solar Array

- Mounting Parts

- Cabling Parts

- Tracking System

- Inverter

- Battery

- Monitoring and Metering Systems

Solar Array

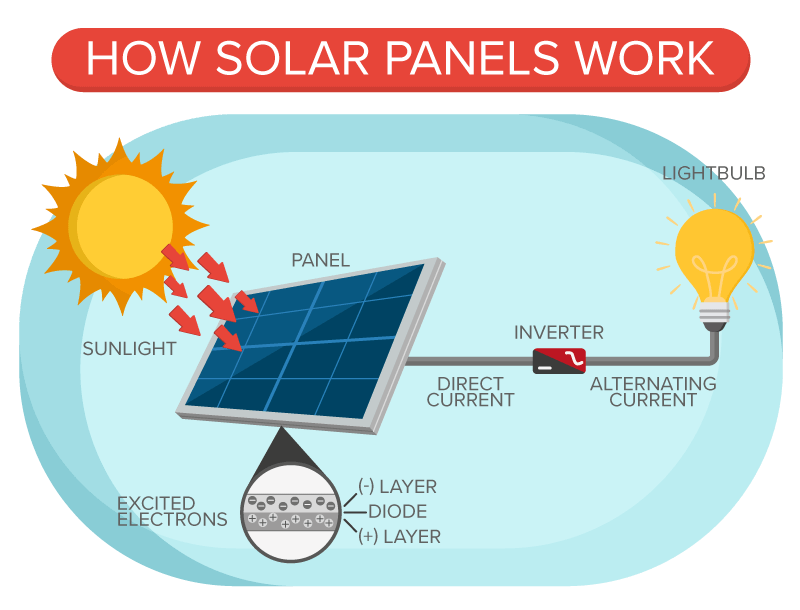

The building blocks of a photovoltaic system are solar cells. A solar cell is the electrical device that can directly convert photons energy into electricity. There are three technological generations of solar cells: the first generation (1G) of crystalline silicon cells (c-Si), the second generation (2G) of thin-film cells (such as CdTe, CIGS, Amorphous Silicon, and GaAs), and the third generation (3G) of organic, dye-sensitized, Perovskite and multijunction cells. Conventional c-Si solar cells, normally wired in series, are encapsulated in a solar module to protect them from the weather. The module consists of a tempered glass as cover, a soft and flexible encapsulant, a rear backsheet made of a weathering and fire-resistant material and an aluminium frame around the outer edge. Electrically connected and mounted on a supporting structure, solar modules build a string of modules, often called solar panel. A solar array consists of one or many such panels. A photovoltaic array, or solar array, is a linked collection of solar modules. The power that one module can produce is seldom enough to meet requirements of a home or a business, so the modules are linked together to form an array. Most PV arrays use an inverter to convert the DC power produced by the modules into alternating current that can power lights, motors, and other loads. The modules in a PV array are usually first connected in series to obtain the desired voltage; the individual strings are then connected in parallel to allow the system to produce more current. Solar panels are typically measured under STC (standard test conditions) or PTC (PVUSA test conditions), in watts. Typical panel ratings range from less than 100 watts to over 400 watts. The array rating consists of a summation of the panel ratings, in watts, kilowatts, or megawatts.

Mounting Parts

Modules are assembled into arrays on some kind of mounting system, which may be classified as ground mount, roof mount or pole mount. For solar parks a large rack is mounted on the ground, and the modules mounted on the rack. For buildings, many different racks have been devised for pitched roofs. For flat roofs, racks, bins and building integrated solutions are used. Solar panel racks mounted on top of poles can be stationary or moving, see Trackers below. Side-of-pole mounts are suitable for situations where a pole has something else mounted at its top, such as a light fixture or an antenna. Pole mounting raises what would otherwise be a ground mounted array above weed shadows and livestock, and may satisfy electrical code requirements regarding inaccessibility of exposed wiring. Pole mounted panels are open to more cooling air on their underside, which increases performance. A multiplicity of pole top racks can be formed into a parking carport or other shade structure. A rack which does not follow the sun from left to right may allow seasonal adjustment up or down.

Cabling Parts

Due to their outdoor usage, solar cables are designed to be resistant against UV radiation and extremely high temperature fluctuations and are generally unaffected by the weather. Standards specifying the usage of electrical wiring in PV systems include the IEC 60364 by the International Electrotechnical Commission.

Tracking System

A solar tracking system tilts a solar panel throughout the day. Depending on the type of tracking system, the panel is either aimed directly at the Sun or the brightest area of a partly clouded sky. Trackers greatly enhance early morning and late afternoon performance, increasing the total amount of power produced by a system by about 20–25% for a single axis tracker and about 30% or more for a dual axis tracker, depending on latitude. Trackers are effective in regions that receive a large portion of sunlight directly. In diffuse light (i.e. under cloud or fog), tracking has little or no value. Because most concentrated photovoltaics systems are very sensitive to the sunlight's angle, tracking systems allow them to produce useful power for more than a brief period each day. Tracking systems improve performance for two main reasons. First, when a solar panel is perpendicular to the sunlight, it receives more light on its surface than if it were angled. Second, direct light is used more efficiently than angled light.

Trackers and sensors to optimise the performance are often seen as optional, but they can increase viable output by up to 45%. Arrays that approach or exceed one megawatt often use solar trackers. Considering clouds, and the fact that most of the world is not on the equator, and that the sun sets in the evening, the correct measure of solar power is insolation – the average number of kilowatt-hours per square meter per day. For the weather and latitudes of the United States and Europe, typical insolation ranges from 2.26 kWh/m2/day in northern climes to 5.61 kWh/m2/day in the sunniest regions.For large systems, the energy gained by using tracking systems can outweigh the added complexity. For very large systems, the added maintenance of tracking is a substantial detriment. Tracking is not required for flat panel and low-concentration photovoltaic systems. For high-concentration photovoltaic systems, dual axis tracking is a necessity. Pricing trends affect the balance between adding more stationary solar panels versus having fewer panels that track.

Inverter

Systems designed to deliver alternating current (AC), such as grid-connected applications need an inverter to convert the direct current (DC) from the solar modules to AC. Grid connected inverters must supply AC electricity in sinusoidal form, synchronized to the grid frequency, limit feed in voltage to no higher than the grid voltage and disconnect from the grid if the grid voltage is turned off. Islanding inverters need only produce regulated voltages and frequencies in a sinusoidal waveshape as no synchronisation or co-ordination with grid supplies is required.A solar inverter may connect to a string of solar panels. In some installations a solar micro-inverter is connected at each solar panel. For safety reasons a circuit breaker is provided both on the AC and DC side to enable maintenance. AC output may be connected through an electricity meter into the public grid. The number of modules in the system determines the total DC watts capable of being generated by the solar array; however, the inverter ultimately governs the amount of AC watts that can be distributed for consumption.

Maximum power point tracking (MPPT) is a technique that grid connected inverters use to get the maximum possible power from the photovoltaic array. In order to do so, the inverter's MPPT system digitally samples the solar array's ever changing power output and applies the proper resistance to find the optimal maximum power point.

Anti-islanding is a protection mechanism to immediately shut down the inverter, preventing it from generating AC power when the connection to the load no longer exists. This happens, for example, in the case of a blackout. Without this protection, the supply line would become an "island" with power surrounded by a "sea" of unpowered lines, as the solar array continues to deliver DC power during the power outage. Islanding is a hazard to utility workers, who may not realize that an AC circuit is still powered, and it may prevent automatic re-connection of devices.

Battery

Although still expensive, PV systems increasingly use rechargeable batteries to store a surplus to be later used at night. Batteries used for grid-storage also stabilize the electrical grid by leveling out peak loads, and play an important role in a smart grid, as they can charge during periods of low demand and feed their stored energy into the grid when demand is high.

Common battery technologies used in today's PV systems include the valve regulated lead-acid battery– a modified version of the conventional lead–acid battery – nickel–cadmium and lithium-ion batteries. Compared to the other types, lead-acid batteries have a shorter lifetime and lower energy density. However, due to their high reliability, low self discharge as well as low investment and maintenance costs, they are currently the predominant technology used in small-scale, residential PV systems, as lithium-ion batteries are still being developed and about 3.5 times as expensive as lead-acid batteries. Furthermore, as storage devices for PV systems are stationary, the lower energy and power density and therefore higher weight of lead-acid batteries. PV systems with an integrated battery solution also need a charge controller, as the varying voltage and current from the solar array requires constant adjustment to prevent damage from overcharging. Basic charge controllers may simply turn the PV panels on and off, or may meter out pulses of energy as needed, a strategy called PWM or pulse-width modulation.

Monitoring and Metering Systems

The metering must be able to accumulate energy units in both directions, or two meters must be used. Many meters accumulate bidirectionally, some systems use two meters, but a unidirectional meter (with detent) will not accumulate energy from any resultant feed into the grid. Frequency and a voltage monitor with disconnection of all phases is required in solar power and it is being generated so that can be accommodated by the utility, and the excess can not either be exported or stored. With variable renewable energy, storage is needed to allow power generation whenever it is available, and consumption whenever needed. The two variables a grid operator has are storing electricity for when it is needed, or transmitting it to where it is needed. If both of those fail, installations over 30kWp can automatically shut down, although in practice all inverters maintain voltage regulation and stop supplying power if the load is inadequate. Photovoltaic systems need to be monitored to detect breakdown and optimize operation. There are several photovoltaic monitoring strategies depending on the output of the installation and its nature. Monitoring can be performed on site or remotely. It can measure production only, retrieve all the data from the inverter or retrieve all of the data from the communicating equipment (probes, meters, etc.). Monitoring tools can be dedicated to supervision only or offer additional functions. Individual inverters and battery charge controllers may include monitoring using manufacturer specific protocols and software. Energy metering of an inverter may be of limited accuracy and not suitable for revenue metering purposes. A third-party data acquisition system can monitor multiple inverters, using the inverter manufacturer's protocols, and also acquire weather-related information. Independent smart meters may measure the total energy production of a PV array system. Separate measures such as satellite image analysis or a solar radiation meter (a pyranometer) can be used to estimate total insolation for comparison. Data collected from a monitoring system can be displayed remotely over the World Wide Web, such as OSOTF.